The UK seaside towns have lost their shine. Once hugely-popular holiday hotspots for working-class Britons, the tourists began to dry up when low-cost airlines made Spain and Italy affordable options for summer jaunts in the 1970s. As the tourists stayed away, so did all their spending money — local economies crashed and these towns became some of the most deprived places in the country. Chief among them were the big coastal towns in Kent on the English Channel: Margate, Ramsgate and Folkestone.

It was an invite to Folkestone which appeared on my desk in the summer, asking if I would like to attend the opening of the Folkestone Triennial 2017. I’ll confess, I didn’t know what it was. The invite was emblazoned with the words “double edge” which shed little light. But I was intrigued, and after Google informed me that artists such as Anthony Gormley and Bob and Roberta Smith were to be exhibiting in the seaside town this autumn, I was sold. Contemporary art by the sea sounded like a winner in my book.

I discovered, via the press release, that the Folkestone Triennial was entering its fourth incarnation and that it was “one of the most ambitious exhibitions of contemporary art outside the gallery context presented in the UK.” This year, there were to be 19 new site-specific commissions installed around the town and that “double edge” was the theme, referring to “the two main axes around which Folkestone’s development as a town has taken place historically and geographically: the seashore and the Pent Stream.”

Folkestone is just 50 minutes away from Central London via the High Speed 1 rail line, so I arrived on the surprisingly sunny opening day in no time at all, and ready to explore. There were a few teething problems; the map was hard to follow, and the signage inconsistent. Perhaps most frustrating was that some of the pieces, specifically Amalia Pica’s Souvenirs — essentially two or three sea shells placed in window sills of shops and houses around the town — are so small and uneventful that once you do track them down, you wonder whether you’re actually looking at the right thing. Two others, Sinta Tantra’s 1947 and Gary Woodley’s Impingement No. 66 ‘Cube Circumscribed by Tetrahedron — Tetrahedron Circumscribed by Cube’ are just existing structures – a concrete office block and a tunnel respectively — given a fresh lick of paint. There’s a whiff of “will this do?” about them.

Those early issues aside, as you begin to tick some of the pieces off your list, you realize that there are some rather striking works included here. Richard Woods’ six colorful mini-holiday home models are a real highlight. Dotted around the town in unlikely places — a roundabout, floating out in the harbor, buried on the beach etc. — they offer a flash of color, an intriguing talking point, and a genuinely political comment on second homes and the current housing crisis in the UK. Siren is a wonderful megaphone-like sculpture by Marc Schmitz and Dolgor Ser-Od , and is inspired by redundant audio technology that can still be found along the coast. It looks like an alien spaceship, but one that is somehow strongly engaged with Folkestone’s past, and with its position high on the cliff facing out to sea, engaged with the town’s geography.

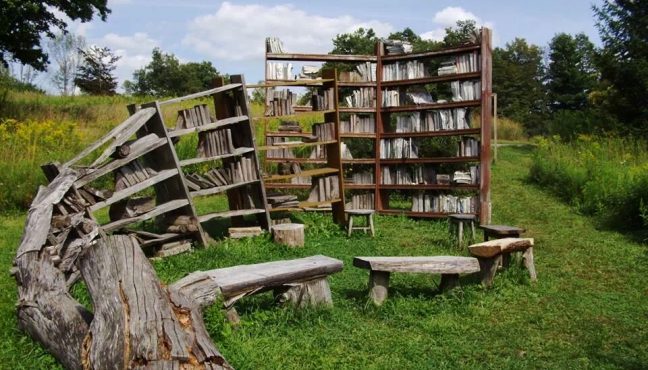

The same can be said for the two pavilions on the beach. Turner-prize nominated artist Lubaina Himid has created a ceramic jelly-mold pavilion that talks to the connections between slavery and sugar. It is also the spot of Folkestone’s former fairground, where sugary snacks were regularly served. It’s a piece you can embrace, where you can sit and enjoy with friends. Similarly Sol Calero’s Casa Anacaona is a brightly colored “social space” that makes you want to strike up a conversation with any fellow visitors. In the sunshine on the wooden benches, it was a genuinely beautiful spot.

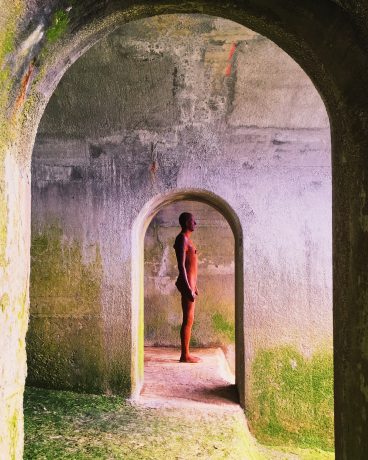

And then, there are the Antony Gormleys. Two sculptures from his Another Time series have been positioned facing out to sea. One is on a loading bay under the pier, standing on green carpet of algae; the other is placed under arches built into the cliff, where you must navigate the rock pools to reach it. Not everyone has been particularly warm to these two pieces, mainly because they have been seen many times before and all around the world (he has cast over 100). But there is something majestic about how they gaze out to sea - the lifeblood of Folkestone — and hunting them out along the beachfront feels like an adventure. With the fresh air, the familiar scent of the sea, and the coast of France so near that you feel you can almost touch it, it really is a wonderful way to enjoy art.

And I think it is the ‘experience’ that makes the Folkestone Triennial. It is not the most picturesque town, but it has a history and a sense of place that brings the narrative together - the “double edge” theme is just an unnecessary curatorial layer. Visitors, many of them here for the first time, will simply enjoy the treasure hunt - exploring the nooks and crannies of the town, and taking in the beach, the pier and the winding streets of the burgeoning Creative Quarter. It is fun, and far less intimidating than walking into a private art gallery.

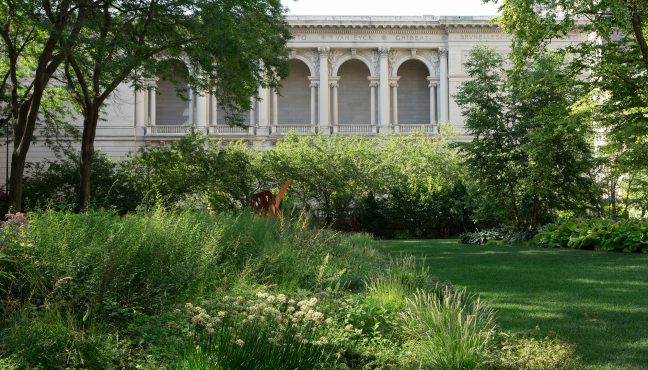

In fact, Folkestone is quickly turning into one of the best ‘galleries’ in the country. There are 27 artworks still in place from previous editions of the Triennial, and a number of the current crop will be added after this edition closes on November 5. Highlights include a simple and moving representation of those killed during WWI by Mark Wallinger, and small bronzes reflecting on teenage pregnancy by Tracy Emin. My personal favorite is Cornelia Parker’s beautiful Mermaid, a reinterpretation of Copenhagen’s famous landmark. This is a town that is packed with art, free for all, and open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. It is a permanent collection that is part of the fabric of the town and part of people’s everyday lives. I’m sure new discoveries are made every day. How many other galleries can say that?

I left the Triennial excited, reminded of the joy of experiencing art in new ways. I was pleased that I’d seen Folkestone, a place I’m sure would never otherwise have troubled my to-visit list. It is an art gallery without walls, in a town that is embracing creativity. I’m sure that visitors will finally be drawn back, and long before the next Triennial in 2020.

The Folkestone Triennial 2017 runs until 5 November. The other artworks mentioned are on permanent display.