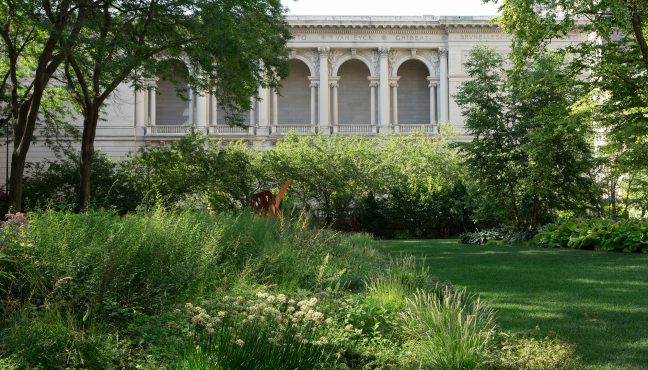

It is one of this autumn’s highly anticipated shows, and a true celebration of British Art and Heritage: Sotheby’s has yet again embedded the stunning grounds of Chatsworth House, a jewel in the heart of Derbyshire, with Beyond Limits: The Landscape of British Sculpture 1950-2015. Showcasing over 30 works of some of the greatest names in modern sculpture, including Henry Moore, Anthony Gormley and Tony Cragg, this exhibition is one not to miss. There is something undeniably exquisite when an exhibition is held on the backdrop of one of Britain’s national treasure houses. We saw similarly in Blenheim Palace, birthplace of Winston Churchill, last year when it was taken over by Ai Wei Wei who filled the inside and outer grounds of the palace with his recent works in his show. Perhaps our excitement, besides the artist and seeing the work itself, is being able to see the art in a completely new setting where we can experience it differently according to the space it is presented. When the space is Chatsworth House, said to be Jane Austen’s visionary inspiration for Pemberley, the stately home of the fictional Mr Darcy, the anticipation for seeing the work is most likely doubled.

Guest curator Tim Marlow who is also the Director of Artistic Programmes at the Royal Academy of Arts comments on the show Beyond Limits, “The relationship of the landscape to the works on display is integral - whether they were directly inspired by or conceived in opposition to the idea of landscape. The result, I hope, will be a sparky, creative conversation between some of the best British sculpture of the last 65 years and one of the greatest of all British country houses and its surrounding landscape.” We were fortunate to be able to visit the gardens of Chatsworth on a particularly fine autumn day and soon found that we could easily spend many hours here walking in and out each part of its expansive gardens. By encountering the sculptures as we took in the fountains, the ponds, the rock garden and whilst even getting lost in the maze, we found that they blended comfortably, becoming part of or coming out from the landscape they were in and even aesthetically echoing and complimenting its surroundings.

Stephen Cox’s Dreadnought: Problems of History - Search for the Hidden Stone (1990-2015) sits at the bottom of The Cascade, a lengthy and horizontal fountain where the water starts from the top of the hill and flows downwards on concrete steps. The fountain itself is beautiful to look at and as we came close to it we found the sculpture on this fountain looking very much like a raw segment of stone, the lines and marks on it indicating signs of possible wear and erode gathered over the years. There is a sense of time through this piece: the 25 years taken to conceive this piece is telling of the artist’s patience,who worked into it gradually, polishing and carving to expose deep into the stone. Cox explains that this rock was quarried in Mons Porphyrites in Egypt, making the artist interestingly the first person to have been allowed to do so since the Roman Empire in 5th century AD. Further to this, Dreadnought is said to be named after a World War I battleship hinting at Cox’s interest in incorporating history into his work. The stillness of the piece is continued in the calm trickling flow through the water, constantly moving and in a sense ageing the stone foundations of the fountain steps.

Not far from the Cascade we entered the Victorian Rock Garden, where massive slabs of rocks are stacked high, one on top of another instigating the child inside me to climb onto the top of these mounds of rock. Once there you could look down through the picturesque trees dappled red and yellow and enjoy from above the beautiful layout of the rock garden. We could spy through the rocks a wooden sculpture. Getting down onto level ground we found Anthony Gormley’s BigGauge II (2014) standing in front of a row of classical head busts. The sculpture is formed through with blocks of cubic squares and cuboids to make the shape like that of a human body, typical to Gormley’s studies throughout his works. The stacked cubic squares and rectangles reflect the stacked piles of rocks behind it, however at the same time the human shape of the sculpture acknowledges the classical busts. Through its surroundings there appears an interaction between nature and the human body. The body is explored in a slightly different light in Sarah Lucas’ pieces Kevin and Florian (2013) which we found at the entrance to the garden’s Maze. The gigantic vegetables were shaped provocatively to become phallic shapes, and Lucas stylistically delivered a humorous take of the human body as well as exploring gender and sexuality. The bizarre humor of these two pieces was carried with us as we got lost inside the maze for a good half hour, getting caught within its deceptive corners and false hopes of finding a way out through the bushy corridors.

What you will not miss in front of the face of Chatsworth House is the long Canal Pond and the Emperor Fountain at the front of it, which altogether makes a splendid view. The Emperor Fountain was engineered to powerfully spout water upwards of up to a record 296 feet. Dotted around the long length of the Pond are sculptures made by equally a dazzling set of huge names in Sculpture. One of these is Dame Barbara Hepworth’s Three Obliques (Walk In) (1969-70) standing impressively at the far end of the pond. Although the size could very well feel intimidating, the large holes cut through them invites the viewers to interact with them. The title gives clues of how we could ‘walk in’ through the pieces. In comparison Richard Long’s Cornwall Slate Line (1990), which lies flat on the ground, quietly mimics the long rectangular shape of the Canal pond. Long has been associated with a genre of Land art and his one passion and inspiration is said to be walking through the countryside and so the placement of his piece here is as if the piece has been returned to where the heart of the idea of its formation was conceived.

One sculpture went beyond reflecting its surroundings and became attached to it. Anya Gallacio’s Blessed (2000) is a piece where metal apples strung onto a real tree, looking significantly bare from its leaves. Everything about this piece seems to accentuate the man-made. The metallic texture of the apples exaggerate the unnatural element as does the contrast of bare branches and the heavy fruit it has apparently born. The fact that this piece has been strung onto a real tree makes us also aware of the action of human interference in nature. Another exquisite piece which communicates human interference is Marc Quinn’s Held by Desire (Square Root) (2014). It is a bronze bonsai tree, gold in colour, placed inside the conservatory, somewhat blending in with other plants. Bonsai trees are grown and maintained under special conditions and treatment to achieve the dwarfish size of the tree and be aesthetically pleasing. Similarly Gallacio and Quinn has used metallic elements to create a replica of something natural but achieves to challenge the way we as humans may have come to change or affect nature in one way or another.

Conrad Shawcross’s piece, The Dapples Light of the Sun I, II, III (2015), was one of our favorite pieces from this show. It is materialized by a chaotic yet strategic steel web of tetrahedrons held up by stands. The sun creates a striking reflection from this steel design from where the title comes from. The height and shape of each of these structures resemble a row of trees, with supposed branches and leaves intruding and intertwining each other, reflecting off the real life trees throughout the grounds. Within the proximity of the sculpture the piece shelters over you and invite you to become a part of it. Shawcross commented that the piece is “a shelter; efficient, interactive”. The energy expressed in this piece leaves a deep imprint from this exhibition: the beauty within this fierce, man-made, and brutal chaos juxtaposed against the natural and peaceful expanse in the background.

Being in its 10th anniversary the Beyond Limits is to date the largest of its series and visitors are spoilt with the offering of truly the best of Modern British sculpture gathered in one space, which we have mentioned only a fraction of. Even for those who had come regardless of the art to enjoy the countryside and appreciate the preservation of the House were able to encounter these works without a feeling evasion which we feel is the beauty of this exhibition. Our day was coming to an end, however there was one last stop we were recommended that we must visit: the Chatsworth Estate Farm House, a ten-minute drive from the House. A large farm dedicated to stocked with locally grown and organic produce, we left with more than we anticipated to, which also included the best pate we’ve ever tried.