Housed in San Francisco Public Library’s old building, the Asian Art Museum cuts a neoclassical figure in the center of the city, far enough from the sea to avoid the throngs of tourists, but close enough to see albatrosses congregating on the fountain in front of the BART station. It’s a 1917 Beaux-Arts construction, with all the grandiosity such a status implies.

The Asian Art Museum (also known as Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture, to distinguish itself from similarly named institutions) outgrew its former home in Golden Gate Park in 2002 and took about a year in order to make the move to its new home, right next to the magnificent dome of San Francisco’s City Hall.

This structure is home to one of the largest collections of Asian art in the world. This may seem strange to an outsider, seeing as five thousand miles of the Pacific Ocean lies between San Francisco and Asia, but it really does make sense. San Francisco is home to the United States’ first Chinatown; the Chinese population is the largest community outside of Asia. This diverse heritage is certainly something that the city is proud of, and is part of its magnetic appeal to everyone from musing beatniks to the throngs of Midwestern tourists who descend upon it every summer. Unfortunately (for us, at least) only 2,000 or so of their 18,000 objects are on display at a time.

The museum could easily fill its three floors with only cobalt-on-white porcelain and Buddha statues, but it takes “Asian” very literally and includes collections that shatter the clichés that the words “Asian art” bring to mind.

In fact, this is the museum’s goal: to approach artwork in a new way, one not constrained by previous assumptions. Sure, there’s a case dedicated to intricately carved netsuke and an entire room of glossy jade implements, among all the other objects one would expect from any given exhibition on East Asian art. But they go much further than that.

For example, there is a sizable space on the second floor dedicated to Philippine art, full of Catholic iconography and some truly incredible textiles, clearly made with astonishing skill. There are also several oil paintings by Philippine artists, which still seems unexpected in spite of the expect-the-unexpected mindset that the museum evokes. There is an association, in my mind, between European art and oils paints. To see such masterworks outside of that context is yet another reminder that Asia (or any other continent, for that matter) is not constrained to any one type of medium or subject matter.

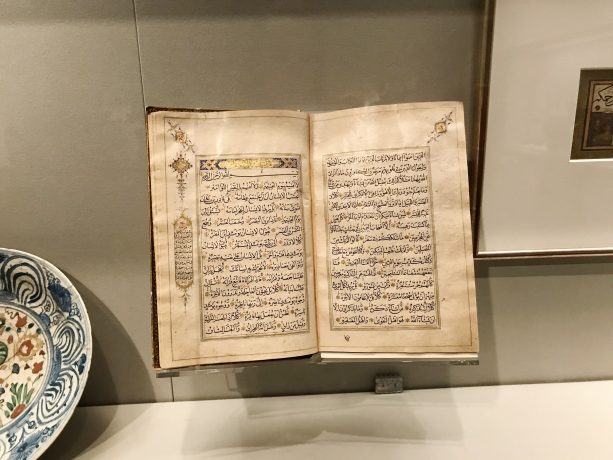

Also present (but somewhat easy to miss) is a varied collection of craft work from the Persian world. The room is packed with quite a mélange: Sassanid coins, elaborate calligraphy tiles, ancient pottery formed after fantastic creatures, a manuscript of the Quran, and quite a bit more characterize the gallery.

Moreover, it would be fundamentally remiss for me not to mention one of my favorite (and altogether unexpected) displays: a cabinet full of Indonesian Wayang golek puppets. They’re strange and delightful things, each with features that communicate a kind of personality that need not be explained with words.

It is important to note that all the galleries are first arranged by location of origin, then split into subgroups determined by a whole plethora of criteria. I found the jade room, located on the third floor, particularly striking. It’s a sort of transition between the gallery of Himalayan art and that of China. The center of the smallish gallery is a glass wall, with jade artifacts embedded in it, like the translucent matrix of an archaeological site. Every shelf is lit from below so that you can fully appreciate the varied shades of the objects.

This very gallery is also an excellent example of the museum’s very intentional use of color in crafting the walls of each room. The ornate metalwork (and a modernist painting or two; more on that later) of the Himalayas is set against a backdrop of rich red paint. As you proceed through the entryway, into mainland China, the walls take on a different mood. Behind the sumptuous jade carvings is a deep blue-gray, signaling that you have left one world and entered another.

After proceeding through there, you’re introduced to some of the most ancient Chinese artifacts, many of which were made before even the Pyramids were constructed. I’ve always enjoyed the seemingly anachronistic relationships between contemporary objects, like what was going on in India as Rome fell? The Asian Art Museum provides a small idea about those often overlooked temporal relationships.

One of my favorite aspects of the museum has to be the Japanese Tearoom, designed by Osamu Sato, a Japanese architect. It was actually created using traditional methods in Kyoto (completely without nails!), then disassembled, shipped to San Francisco, and reassembled. The peaceful aura that it conjures seems to be worth every mile traveled.

Just around the corner from the tea room is the Betty Bogart Contemplative Alcove, a small corner that— even on a busy weekend— manages to be the perfect location for meditation. Art museums so often are aesthetic experiences, with lots and lots of input and not always space to process what you’re seeing.

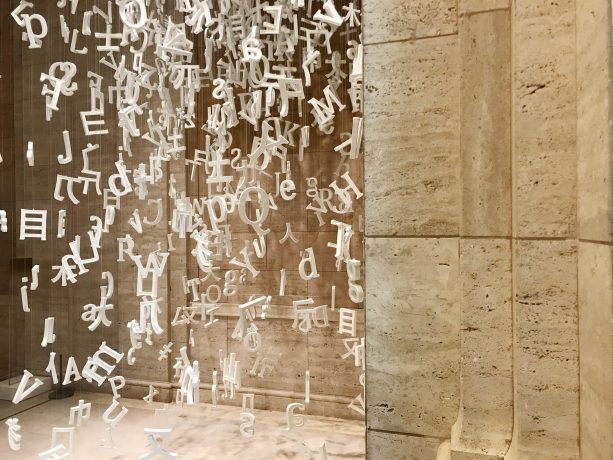

As a whole, the galleries are set up according to the constraints posed by the building. Everything encircles Samsung Hall, a cathedral-like room in the very center of the museum. In a sense, this constraint actually works in their favor; it allows a very set number of entry points into exhibits, meaning that curators can nearly guarantee that the majority of visitors will move in a linear fashion. From there, crafting a cohesive narrative is actually quite simple due to the fact that everyone is moving in the same way.

I like this quite a bit, especially in exhibits on temporal differences of objects within a region. You can observe styles changing, certain motifs going in and out of vogue, sometimes traveling thousands of miles. Cobalt from Afghanistan colors Ming dynasty porcelain, Hindu gods appear in Japanese sculpture, a case is made for tobacco imported from Indonesia. Asia, the largest continent on Earth, isn’t so large after all.