“One needs an exceptionally fine sense both of art and nature if one is to make a harmonious combination of two such seemingly contrasting elements. But once this has been achieved, it often turns out that the one contributes to the other, reinforcing its character. The powerful atmosphere of nature is capable of stripping an artist’s pure creation of even more of its materiality, allowing the idea it contains to achieve an even more forceful expression, while on the other hand an artwork that is deliberately placed can lead extra nobility to a magnificent landscape”. Helene Kröller-Müller

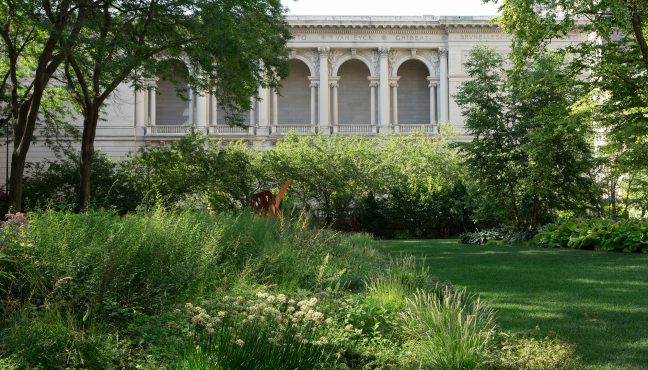

When the Kröller-Müller museum opened in 1938, the high quality of three components was decisive for its success: visual arts, architecture and nature; the three still define the museum’s unique character. Today, the Kröller-Müller epitomizes an art museum in the tranquility of nature, calmness and space. Thanks to the very character and location, the museum offers contemplation, reflection and enjoyment. Those offerings are in ever shorter supply in present day society. Noise, excess, speed, competitiveness, impatience have become characteristic of our every day lives. There is a great need for something to offset them. The Kröller-Müller museum wishes to present itself as a refuge for those seeking peace and quiet, authenticity, display of art in relation to architecture and nature.

The museum buildings moderate the interaction between inside and outside. The sculpture garden, with the sculpture pavilions designed by Gerrit Rietveld and Aldo van Eyck, is another counterpoint in this totality. Even before the sculpture garden came into 'visible', it had been an essential element in the museum's policy for many years. In the history of the Kröller-Müller Museum there was always a policy relating to the extensive nature reserve in which the museum is located. Garden and museum architecture were and still are on equal footing with museum architecture. Once the artist involves nature as an artistic medium, it becomes a very specific project. Over the years, these moments were carefully pursued; that's why the landscape, its presence and its layout have been so loosely involved in the cataloguing of that part of the museum collection.

Museeum has interviewed Jannet de Goede, curator of the Kröller-Müller Museum, and talked about the past, present and future of the garden.

Could you tell us a brief history of the Kröller-Müller Museum. Was the sculpture garden planned from the very beginning?

The initiator and the founder was Helene Kröller-Müller. At some point in her life she decided to start a collection of works which could show people the art since 1850 till her time. She had an educational purpose and she wanted to leave the collection for the Dutch public. Helene wanted to present it in a house museum, that’s how she called it. Hellen and her husband were very rich and they also owned this ground. Helene decided not to build the museum in Den Haag (The Hague), where she was living with her family.

The museum was opened in 1938. Helene died a year later. She was the founder and the base of the museum is her collection. And her successors had to obey her wish to have a collection of artworks, displaying the history of art. They were a little bit limited, because she was very precise on not adding anymore works to her collection. But Prof. Dr. Bram Hammacher (1897-2002), who was director of the museum from 1947 – 1963, saw an opportunity, because she was talking specifically about paintings and works on paper. He wanted to focus on sculpture. In the 1940s and 1950s there was a new idea of sculpture being equally as important as paintings. He was in the middle of this discussion, where all sculptors, museum directors and curators had more attention for this tradition. And of course sculptures were presented during the biennials. He decided to make the / a sculpture garden, to connect nature, sculpture and architecture. He was the founder of the sculpture garden. When it was opened in 1961, it was a really new concept. People were astonished by it, by the fact that you can present sculpture in a natural environment in this way. Of course nature was artificial, it was a garden. Rudi Oxenaar (1925-2005) was the next director of the Kröller-Müller Museum (from 1963 until 1990). Oxenaar bought works by large scale sculptors, such as Richard Serra, Claes Oldenburg, Jean Dubuffet. He expanded the sculpture collection into the field of land art.

And also expanding the museum space.

Yes, indeed. The first sculpture garden was 4 hectares. He doubled it. He was even dreaming about expanding it across the whole park, but never succeeded in it. There are some works of art outside of our park: like the one by Henry Moore.

I think back then beside the fact that land artists were land artists, they also didn’t want to be exhibited in white cube spaces. It was a perfect place for them to be and to be a part of the museum collection.

It was a beautiful combination: the wish of the sculptors, opportunity given by this place and the director. There were of course more directors back then, who were choosing the similar politics. But Hammacher was the founder of the idea of the sculpture garden in the modern sense of the word. You had gardens with sculptures before (Versailles, etc). But he opened a sculpture garden.

Was Louisiana Museum in Denmark opened later?

Yes, it was actually based on the Kröller-Müller concept. The garden by Hammacher is totally different from what you see now. Besides the Marta Pan, who is still there. The further you go, the more changes you see.

So were the displayed works being changed? Or there were new acquisitions?

At first when he started to collect for the sculpture garden being built, he displayed the sculptures on a grass loan in front of the museum. A lot of them are still there. With Oxenaar things have changed, it became more flexible.

There are some different works which are not on permanent display. Nowadays the garden is opened the whole year around. This is something which was initiated by Evert van Straaten (director of the museum from 1990-2011). Until the 1980s-1990s it was closed during winter. The works were moved inside because of the weather, that’s why there could be changes in the exhibited works during different seasons.

What was the idea behind placing certain works in certain places of the garden? Obviously they are communicating with each other.

Hammacher was not consulting artists, when he was placing the artworks in the sculpture garden. There was one exception: tFloating Sculpture ‘Otterlo’ (1960-1961) of Oxenaar had a dialogue with different artists. For example, the placement of the work by Richard Serra is very specific. It was pointed out by Serra. His work Spin Out (for Robert Smithson) (1972-1973) is site-specific.

Are you working on the new acquisitions? What are the main functions of your department?

A new work by Pierre Huyghe was bought last year by our recent director Lisette Pelsers. It’s being made now, it’s a garden. It’s called La Saison des Fêtes. It will be opened for the public at the start of summer 2016, because different plants have yet to be planted. Beginning of July we will have a special moment when we will officially present this work of art to the public. It is more like a landscape environment space. And in the middle of it there will be a garden. This is one of the new acquisitions.

So in this piece artist is giving instructions about how to make the artwork and museum is fulfilling them.

Yes. It is an existing work. It is edition. It has been exhibited indoors earlier in Madrid . But the artist liked the idea to show it outdoors. Huyghe is instructing our gardeners how to make the artificial landscape and plant the plants he wishes. It will be very beautiful. We have the artwork “Jardin d’email” (1974) by Jean Dubuffet, which is also an artificial garden, in which you can walk. This is also the case with the work by Huyghe, although it is derived from a totally different way of thinking. It is a big circle with 12 segments. Every segment symbolises a month of year. Every month has its different blooming plant: daffodils in spring, pumpkins in November. All those flowers and plants say something about a special day, celebration day somewhere in the world religious (for instance Christmas or Pesah) or secular (such as Valentine’s Day or Halloween).

How do you think art and architecture, placed in the context of nature, influence visitor’s perception of art?

The wish of the founder of the museum, Helene Kröller-Müller, was to create a museum right in the heart of nature, where people can go and leave their everyday thoughts and problems behind, go into this relaxing atmosphere, where you can be more open to get the message of the artist. I think it works like that. The moment you go through the gate, you open up. It’s quite extreme here, because the museum is surrounded by the park. This combination of nature, quietness, isolation works. It was the wish and the concept of Helene Kröller-Müller and it still continues to be this way. It brings people the idea of an essence of where art, nature, sculpture, architecture can meet.

Stories behind our favorite artworks:

Rudi Oxenaar, once director of Kröller-Müller museum, was fascinated by the fact that three-dimensional projects by the famous painter Jean Dubuffet were not only sculpturally, but architecturally conceived, as well as undoubtedly being utopian. About this noticeable shift from flat plane to three dimensional, Dubuffet wrote: “Is it inaccurate to describe my paintings as a model for “Jardin d’émail?” I don’t think so. Who has decided that a painting can only be vertically on the wall? You can just as easily see it if it lies flat on the table”. Oxenaar was intrigued by the fact that the strictly anti-natural intention of the work would form a splendid counterpoint to the surrounding nature He described is as a “walled meditation garden”.

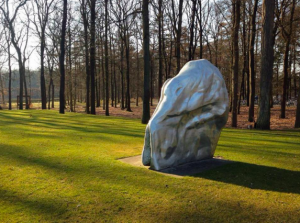

Sculptures by Marta Pan were organic, usually wooden shapes whose dimensions were those of humans. They were inspired by the themes of “equilibrium” and “pivot”, and served as a source of inspiration for choreographers. Hammacher decided to commission a piece from Marta Pan. He wanted a work that would link three elements to one another: the museum, the garden and a pond.

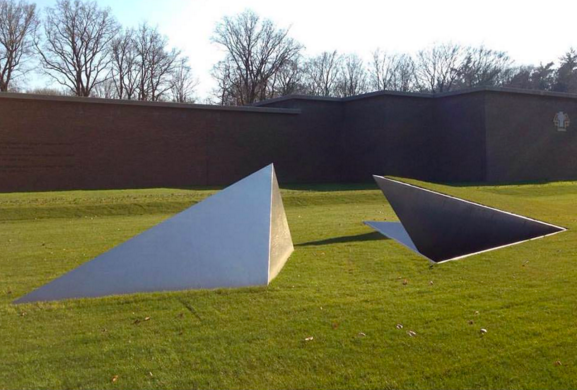

On the edge of the sculpture garden, close to the French hill, is “Spin out, for Robert Smithson”, the first land art project the American artist Richard Serra made in Europe. It consists of a natural bowl- shaped hollow, one side steep and completely overgrown with trees, the other side lower, while three steel plates, roughly the same distance apart, project from the surrounding slope.

When director Rudi Oxenaar invited Serra to make a work for the sculpture garden in 1972, it was the latest development in the artist's work – his radical interaction with landscape. Since 1969 Serra had regularly been drawing attention from the art world with his so-called Props – unusual sculptures in which he confronted the viewer with leaning or hanging materials , balanced in an often life-threatening manner.

In 1986 Rudi Oxenaar invited Krijn Giezen to design an “observation post” for the French Hill, a 20 m high dune in the new part of the sculpture garden. Krijn Giezen designed the installation “Kijk uit attention” between 1986 and 2002. When the artist began designing the staircase, no one could have foreseen the problems the project would bring with it, let alone the long-drawn-out saga it would become. Design plans and model were ready quite fast, but the higher costs and lack of exact planning permission meant the work could not be constructed in the foreseeable future.