Venice in winter for those who have never visited this magical city, might mean houses rotten from water damage, bulged and sloping walls, uneven roofs with rain and snow leaking in… water as a source of danger or at least discomfort. In order to realize that the city is not sinking, but floating, and not sad, but happy you might need to either take a look at the carnival photos (it takes place February 11-28), or, even better, visit Fondazione Querini Stampalia where water serves an architectural inspiration.

Water is a mirror of the palace outside, it enters the building through internal partitions along the walls, it irrigates and frames the garden in a large multi-level tank, made of copper, cement and mosaic and in two alabaster and Istrian stone labyrinths, where water becomes calm and ends up as water lilies. The ingenious design belongs to Carlo Scarpa and Mario Botta, who worked on the palazzo at different times, but together made this place a perfect example of the aristocratic, exquisite Italian architecture.

It all began in the 16th century, when the Palazzo was built in the heart of Venice just a few steps away from the central Piazza di San Marco. It used to be a family home for the prominent Venetian Querini Stampalia family, considered one of the families that founded the city. Its last descendant, Count Giovanni, created the Foundation Querini Stampalia in 1868, but died the following year without direct heirs. However, he left a testament, where he ensured that the house would become a museum and the library would be opened to the public every day until late night, including public holidays. The House-Museum has been open since 1869 letting the visitors be a part of the noble Venetian lifestyle with its 18th century furniture, porcelain, sculpture, and paintings (14th to 20th century), including works from Giovanni Bellini, Lorenzo di Credi, Jacopo Palma il Vecchio, Bernardo Strozzi, and other representatives of the Venetian school. The library holds 370 000 volumes including the original nucleus of the collection containing family documents, manuscripts, sixteenth century papers and documents, it constantly grows and anyone can visit!

At the beginning of the 20th century Pinacoteca Querini Stampalia was not in the best shape; in 1949, the Governing Body of the Foundation decided to start restoration work on the ground floor, which was unused at that time due to frequent flooding, and the neglected garden behind the palazzo. The work was commissioned to Carlo Scarpa who delicately preserved what could’ve been saved and introduced new elements translating his interests in history, invention, and his love for nature into an ingenious project.

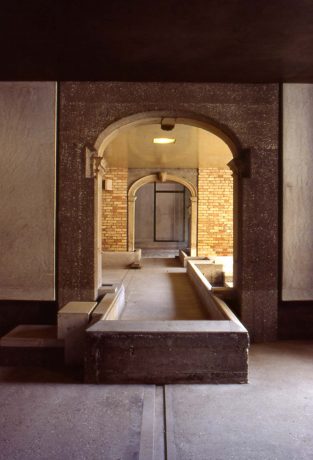

Carlo Scarpa’s restoration started with the removal of some later decorations, stabilization of the existing walls, and careful cleaning of the ancient architectural features. The architect built a wooden bridge and made a new entrance from what once was a window. He put a crystal door with a couple of steps leading to the courtyard, which has a mosaic floor of red, pink, white and green marble tesserae. The ceiling is made of red stucco, with plaster panels on the walls. The restoration was intended to respect the old architecture, fortifying it with new elements, but with a distinction between the existing and the new.

The central path and the staircase in stone covered cement was created to regulate the water that floods the ground floor when there is the phenomenon of “high water” in the lagoon. This underlines Carlo Scarpa’s respect for natural elements – water can flow into some spaces, creating harmony with the building. Naturally, the system prevents water from entering the exhibition area, it only frames the palazzo. Water is an essential element of the garden, which stretches between the land side of the palace and a high perimeter wall. The elegant garden was once neglected, but now it is a unique courtyard that manifests the architect’s love for Japan (that he studied and visited many times) with a cherry tree, magnolia, and pomegranate. Set into the wall is a mosaic designed by Mario De Luigi made of a tesserae of gold, black and silver Murano glass. Glass and concrete underline the fragility and value of nature and art.

The next phase of the architectural and functional recovery was undertaken for 50 years and lasted until 2013. In the 1990s, Mario Botta, who’s thesis adviser was Carlo Scarpa, started the renovation. The architect was motivated by his love for Querini Stampalia not only because of Carlo Scarpa, but also due to his gratitude for the hospitality that the institution had offered him in the years when he was in Venice to major in architecture. So, it should be mentioned that the great Mario Botta chose to work free of charge.

Mario Botta chose to use Carlo Scarpa’s materials and architectural techniques that gave a sense of succession and continuity; his renovation of the attic and the third floor allowed to obtain more space for new offices, exhibitions and contemporary museum needs. Mario Botta also moved the main entrance to Campo Santa Maria Formosa and managed to preserve Carlo Scarpa’s works from continuous functional adjustments. All services moved to the ground floor: foyer, ticket office, cloakroom, bookshop, café, elevators and area for children. The project also included an innovative auditorium for major lectures and events that today attract locals, tourists, young and old.

The museum is an example of a delicate relationship between the two major protagonists of contemporary architecture, and is a pleasure for any museum-goer. Carlo Scarpa and Mario Botta perfectly elaborate and enrich the beauty of the 16th century palazzo, making it a great example of a contemporary museum: inspiring, informative, comfortable, technologically advanced and fun!